‘Progressives’ have always hated prisons. Always. There’s a very simple reason for this, which is that prisons are ugly. They address a difficult problem that we wish didn’t exist: what do we do with bad people?

I know, I know. I’m simplifying here. Criminals aren’t ‘bad’ people—they’re people who do bad things. Some people might even argue that ‘bad’ things aren’t inherently bad; they’re only bad because society has decided that they are bad. We don’t have to go there.

However you define it, the fact remains that we cannot have a free and healthy society unless we can agree upon some system of dealing with the people who go against the morals and values of that society. Without some type of ‘justice,’ a community devolves into chaos. Just look at New York since they got rid of bail.

However, what’s interesting about a society’s methods of punishment is that people who live in that society kind of believe that the current method of addressing such issues is the only possible method. When we think of criminal justice, we think of prisons. That’s how we deal with criminals, and it’s how we’ve always dealt with criminals, right?

During my one-year stint in law school, I had a Criminal Law professor who considered herself a ‘prison abolitionist.’ Yes, she was very liberal, and yes, I strongly (and silently) disagreed with her about her opinion on this issue. And I’ll stand by that—for all of her (valid) talk about how horrible prisons are, she offered very little as to what they could possibly be replaced with, besides vague mention of undefined ‘social programs’ to turn criminals into upstanding citizens.

Philosophical arguments about whether deviance can be entirely eradicated aside, what my professor failed to address was what those social programs might look like.

The prison industry (and I use that term deliberately) was actually instituted as a type of progressive reform—a rehabilitative alternative to the brutal methods of punishment used in the 17th to 18th centuries.

Although my professor fell into the trap of the well-meaning idealist, she was not wrong to suggest that the system could be changed. After all, the prison itself is a relatively modern phenomenon. Actually, I won’t say that. This depends what you mean by modern. There were prisons in ancient Rome, Greece, and Egypt. The idea of a place to hold convicts is not a new invention, although it fell out of favor for a while (we’ll get to that).

Similarly prison labor is a very old concept (and we all love to hate the Prison Industrial Complex). Convicts in ancient times were often sentenced to hard labor as punishment for their crimes. In the Middle Ages in Europe, criminals were sold into slavery.

However, if we forget about antiquity and look at the history of the last few centuries, prisons are pretty new, and came about as a progressive invention. In the United States, prisons didn’t really come about until the late eighteenth to early nineteenth century. Before that, the long-term detention of criminals wasn’t done. Punishment was brief—it typically either consisted of public beating and humiliation, or execution if the crime was particularly egregious.

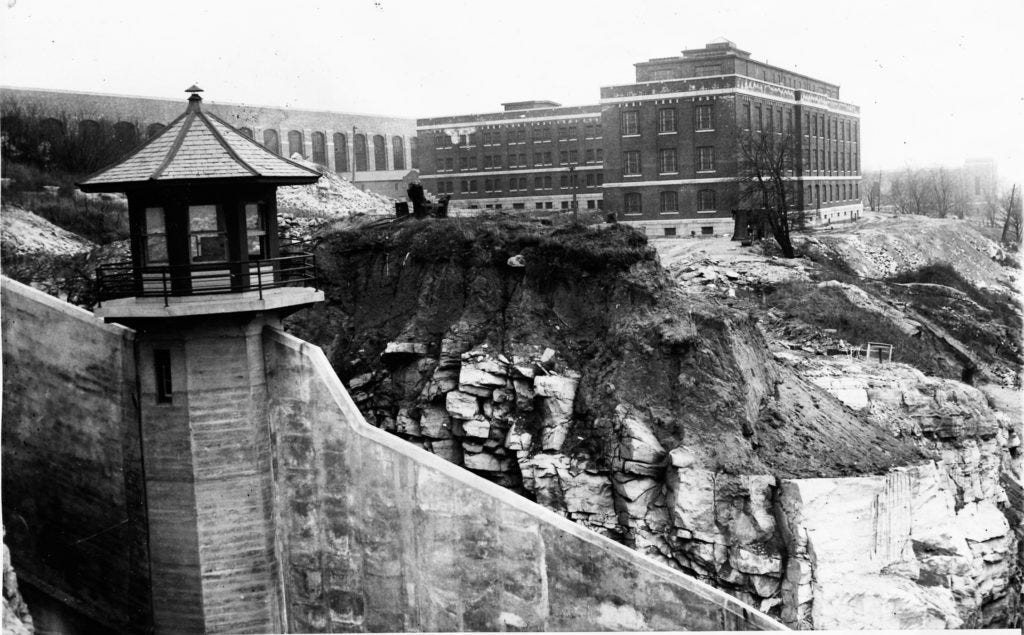

When New York started its prison system in the 1800s to offer convicts a more humane alternative to the brutal punishments of either public floggings or death, work was instituted as something to keep the inmates busy, a humane alternative to idleness that would have the added rehabilitative benefit of instilling in prisoners a set of values that more closely aligned with mainstream society.

That was the alleged purpose, at least. Of course, the road to Hell is paved with good intentions (or, perhaps, the empty promise of good intentions), and the old prison-work system has devolved, like the rest of America, into a corporate cesspool in which prisoners are treated like cattle, abused for profit and neglected when they are no longer useful.

There’s nothing new under the sun, as they say, and this mistreatment of prisoners is also a very old concept. In the late 1800s, American prisons leased out their prisoners to industrialists, who desired these laborers precisely because they worked longer hours for less pay, and could be beat and otherwise abused. When this was changed and prisoners had to do their work inside the prison, conditions hardly improved.

And just as reformists tried and failed to change it then (prison reform was a hot topic in the early 1900s—New York governor Al Smith, for example, advocated strongly for prison reform, and did perhaps improve the situation temporarily), so too are prison reformists today likely to address minor changes that don’t really get at the core issue, which is that the punishment of crime is an ugly thing.

There are a lot of factors at play here. For one, politics, in addition to being egregiously corrupt, is a slow, clunky system—in all the compromises and roadblocks that reformers encounter as a matter of course, it’s hard to get anything done.

More importantly, though, no one has ever been able to come up with a desirable system for punishing crime. Beatings shock the conscience, but so do life sentences. Labor is exploitative, but idleness is maddening. ‘Conditioning’ is a pipe dream. What do we do?

Am I saying that prisons couldn’t be better? Obviously not. What I’m saying is that throughout history, the ‘humane’ treatment of criminals has always been a hotly debated issue, and no one has ever really gotten it right.

It’s a largely subjective question. One could even make the argument that this old system of either a quick flogging or a quick demise was more humane than the morally reprehensible one we have today. Most people would disagree with this, of course, but the argument can still be made.

Perhaps it’ll come back around. First we’ll let everyone out of jail, then, when things get really bad and the prisons are all gone, there will be public executions on the streets. Then, when people cry for reform, the prisons will open back up again, and the cycle will begin anew.

Such is life.

References:

Time Magazine, “The True History of America’s Private Prison Industry,” by Shane Bauer (2018).

correctionhistory.org: “Evolution of the New York Prison System.”

Harry E. Barnes, “The Origins of Prison Reform in New York State.” The Quarterly Journal of the New York State Historical Association (1921).

Mary Gibson, “Global Perspectives on the Birth of the Prison” The American Historical Review (1921).

Henry Theodore Jackson, “Prison Labor.” Journal of the American Institute of Criminal Law and Criminology (1927).

How to deal with people who abuse their social contract with the community is a hard question. Certainly, the way prisons are run and the social safety net of former inmates can be better. But these initiatives are themselves subject to the very forces that led to criminality. The Christian Worldview uses the unlovely term “Sin” to describe that quirk in human nature that produces the sins the community is trying to eradicate. Unfortunately, too many prison officials, guards, and various individuals connected to the “prison industry” dismiss that description of human nature as it is applied to them. They are unconscious disciples of Enlightenment thinking that declared the death of Man’s inherent sinfulness in favour of basic goodness, needing only the proper circumstances for the goodness to be realized.

In this new paradigm, criminality becomes a social issue instead of a moral issue. The prison industry is tasked with the job of providing those favourable circumstances through which the inherent goodness of the criminal can be expressed. The entire industry has worked on this file with little success for three hundred years, with little to show for it.

It is interesting to me that jails allow Christian chaplains as a normal modus operandi. I have applied myself to volunteer as a friend to inmates, weekly visiting them over closed-circuit TV. My surprise comes from the lessening of Christian influence in much of our Western society lately. Could it be that Christian programs have been shown as one of the more successful approaches in relation to any freedom from reoffending?

(See https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-1-4614-8930-6_1)

What came to mind when I was reading this was my classes on rehabilitative vs restorative vs retributive justice in my conflict transformation program. It raises the fundamental question of "What is the role of justice?"

I think it's an important question to consider. The obvious answer is that, like you said, it maintains order that is attuned to social morality. But that opens the question, "What is our morality?" And "how does justice maintain order and morality?"

The fundamental idea in much of jurisprudence is to "make whole" the victim. Of course, there's plenty of cases where that is not possible. The idea then is to enact a punishment which seems befitting a crime. This is an attempt at satiating the anger and desire for retribution.

What then of the reality of the victim and criminal? Despite the justice system, they both walk away worse off. The criminal is subjected to the brutality of prison, and the victim must resign themselves to whatever closure the sentencing may give them.

Restorative justice, as most famously executed in Rwanda and South Africa, focuses on bringing the victim and perpetrator into a reconciliation of the harm that has occured. The hope is that this brings closure to the victims, and that the perpetrator may redeem and rehabilitate themselves.

A friend, however, put across a pertinent question. What of a crime like rape? How does one reconcile such a brutal and senseless act? At the time, I agreed that this was probably an exception to the idea of restorative justice. But the more I work with the aggression and anguish, the more I'm beginning to wonder, if cases like that too can be seen through restoration.

Of course, at the end of the day, it depends on the prevailing jurisprudence. I agree with you that we cannot do away with the prison system with our current justice system. Perhaps human beings never will be able to.