“Other people write about the bling and the booty. I write about the pus and the gnats. To me, that’s beautiful.”

This quote was uttered by the songwriter Vic Chesnutt, but it’s the sort of thing that I could imagine being said by many artists—namely Philip Guston, a painter for whom pus and gnats would be considered tame subject matter. Guston didn’t shy away from life’s grotesque imagery, and it’s this boldness which lends the artist his power.

It is cathartic to see our most uncomfortable emotions expressed outwardly before us. This idea goes back as far as Aristotle, who theorized in his Poetics that the purpose of tragedies is to offer “purgation” of such emotions as “pity and fear.” The artist feels lighter after transferring these emotions onto the page or the canvas. The viewer can find comfort in seeing his demons expressed before him. It’s a type of solidarity; seeing our anguish spelled out before us makes us feel less alone.

This may be where the trope of the ‘tortured artist’ comes from. We all have an idea in our heads of what this character looks like. The frustrated writer, holed up in a dark, dingy apartment, succumbing to addiction and self-indulgence, never picking up a pen. The agonized painter, awake until sunrise and asleep until sunset, huddled over his canvas day in, day out, only to decide that his work isn’t any good and splatter red paint over the whole thing. There’s a reason we’re so familiar with this figure—countless paintings and novels and songs have been created in its honor. But there’s a strange second layer at play here.

These works are semi-autobiographical in nature. They ‘purge’ the dark side of their creator. Interestingly, though, there lies within them a sort of inherent contradiction. In order to create anything, an artist must overcome stagnation. At some point, if such a work is ever to be made at all, an artist needs to have given up his self-indulgence and sat down to do his work. Thus, in all artworks of this kind there is an unseen success story, a victory over the very pain this art is expressing.

Some brilliant artists, like Guston, have made careers out of giving a voice to discomfort. Take, for example, Vic Chesnutt, the brilliant musician whose quote began this article. If anyone has the right to call himself a ‘tortured artist,’ it’s him. Rendered a quadriplegic after a drunk-driving accident when he was just eighteen years old, Chesnutt spent his life overrun by medical bills, threatened by a worsening condition with no hope of improvement. Unable to even hold a guitar pick, Vic had to invent his own method of playing the instrument.

A weakness can become a strength, however. In the songs that just feature him and his guitar, he was forced into a minimalist style that only aided his art. Each note feels deliberate—which is true, since each note is difficult to play. Such songs are quiet; they contain a lot of ‘empty space.’ They are powerful; they hit you straight in the soul.

My favorite album of his, though, is one in which he relied on others for help. It’s his penultimate album At the Cut, released in 2009 and recorded with the brilliant Silver Mt. Zion Orchestra, who were a perfect complement to Vic’s hard-hitting songwriting. They released the album in the same year Vic died by his own hand, motivated by an ever-growing pile of unpaid medical bills. The album is dark, grappling with emotions like fear, sadness, and death, and its backstory makes it even darker. However, despite (or perhaps because of) its somber imagery, the album is the perfect soundtrack to a lost, lonely evening. It is healing music—a balm for all the emotions that it describes.

A highlight of the album is titled “Philip Guston.” The song is an apt tribute to its namesake. Featuring long sections of wailing violin and distorted guitar, its sounds are jarring on their own, but when they come together, they overwhelm the senses in the best kind of way. The song’s overt use of ‘uncomfortable’ sounds bears a resemblance to Guston’s own use of unsightly colors and disturbing imagery. Vic was a fan of Guston, and in this one song, he managed to capture the ‘essence’ of this work in audible form, illustrating how an artists’ message can transcend mediums. The song is brilliant in and of itself, and it becomes even more brilliant when the artist to whom it pays homage is taken into account.

It’s funny—I’ve always loved the song, and yet I’d never once sought out the work of Philip Guston until one trip to the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Overall, it was a negative experience. A cacophony in the worst sense of the word. There were too many people, too many cases full of trinkets like rocks and brooches. Too many pieces of cracked, weathered pottery cluttered what would otherwise be cool exhibits. And it seemed like every time I was immersed in a painting or sculpture, someone would take a selfie in front of it. In some darkly comedic way, the museum is like an artwork in itself, a twisted tribute to the city that it inhabits. It contains some of the greatest works of art in the world, yet despite its massive budget, it seems like the pieces are hoarded, not curated. And the predominant sentiment within the place seems to be “what a cool painting—look at how beautiful I look standing next to it.”

Anyway, I was wandering around my favorite part of the museum (the section of European paintings on the second floor), and stumbled upon a peculiar exhibit, titled “Philip Guston: What Kind of Man Am I?” Located right next to the Monets and the Renoirs and the other colorful landscapes and striking portraits, here was a different type of art. The room was more sparsely populated than most (both with paintings and with people). It was humbler, less flashy. I was about to pass it over entirely when I noticed out of the corner of my eye the artist’s name on the wall.

Vic Chesnutt’s song started playing in my head immediately. It’s an easy song to replicate. The intricate musicianship of Silver Mt. Zion is impossible to reproduce from memory (part of what makes the album so re-listenable), but Vic’s two repeating notes which continue throughout the song are fully committed to my memory. So these notes played, and meanwhile I looked at the paintings. The first one that caught my attention was Painter’s Hand, pictured below. “The hand” is a repeated lyric in Vic’s song—I assume this was the very hand that inspired it.

It deserves the attention it receives. It’s a quintessential “Portrait of the Artist.” After all, it depicts the exact part of his body that performs the artist’s labor. And it’s not portrayed favorably, either. The hand is not soft or delicate or elegant. It is red, veiny, ugly, distorted. It’s gruesome, really; the viewer can feel the pulsating aches in its swollen veins. The whole canvas emits a gut-wrenching pink-and-red hue (a motif that connects many of Guston’s paintings). It suggests that creating art is something agonizing and strained.

Philip Guston, Painter’s Hand, 1979.

Philip Guston, The Line, 1978.

The next repeating lyric in the song is “the line.” This is the title of a Philip Guston painting, too, and interestingly, it’s a painting of another hand. This time, the hand is emerging from a cloud, drawing a straight line on the ground. This painting seems to be an almost optimistic counterpart to the first. This hand also features giant protruding veins that give the appearance of strain. But the bloody red tint is absent, and the cloud alludes to something divine. Is Guston suggesting some metaphysical origin of artwork, some faith in a higher guiding force? Perhaps. But both paintings argue the fact that creation is hard. I wonder if this is why Vic was so drawn to them (after all, his disability made the physical act of creation more difficult for him than most). Still, nearly any artist can relate. I can’t imagine anyone who’s ever labored over their craft looking at these paintings and seeing anything except themselves.

The ‘tortured artist’ motif spanned the best paintings in the collection. It seems Guston had a penchant for self-portraits. My personal favorite, titled Pittore, depicts the painter lying in bed, a cigarette protruding from his mouth, the same pink-and-yellow veins which spanned his hands now populating his forehead and eyes. A clock sits before him, mocking him. Once again, the colors of his skin spill out into the room around him. His eyes are wide open, exaggerated. The paintbrush lies next to him untouched.

Philip Guston, Pittore, 1973.

The whole thing is cartoonish and kind of ugly, yet I could have stared at the painting for hours. I think it’s because it depicts a familiar experience—a torturous night in bed, too preoccupied by thought to work, too preoccupied by work to relax and sleep, taunted by the clock and by a habit that fails to deliver its promise of numbing the pain of inaction. I guess this is the common thread which connects creatives and utter lunatics. Art is generated under duress, usually, if not by a deadline then by a nagging feeling that if a thought is not expressed outwardly (perhaps on page or canvas) the clattering in one’s mind might become deafening. You have to be a little off to want to sit down for hours by yourself and create anything. Most people wouldn’t dare observe the inner workings of their minds for that long.

Still, some artists are more temperate than others, and some are prone to agonizing self-indulgence. What makes some artists damned to dark, twisted imagery, while others are able to produce things of optimistic beauty? Why are some prone to “bad habits”—another mantra that Vic repeats over and over again in his song?

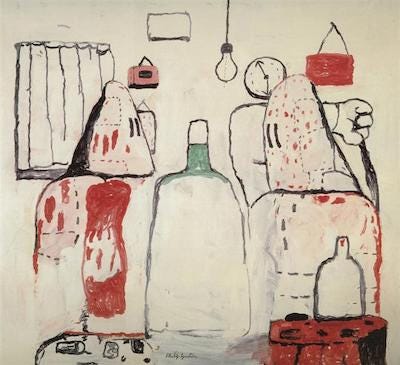

Philip Guston, Bad Habits, 1970.

Guston’s Bad Habits depicts two cloaked, blood-splattered Klansmen sharing a bottle of liquor. Its implications are horrific. A pair of murderers coming home after their dark duty is done, indulging in a celebratory vice. One of the men is scratching his back, indicating a relaxing end to a hard day’s work. Once again, there’s a clock, but this time it doesn’t seem to be tormenting them. Instead, it almost serves as a reminder of the banality of all of it, like their murder is just ‘another day on the job.’

Let’s think about the title: Bad Habits. One interpretation of this title is the obvious ‘bad habit’ of drinking depicted in the picture. But there’s potentially a second meaning here. A religious habit is a uniform manner of dress worn by members of a religious order. Might the white cloaks that the men are wearing be a type of ‘habit’ themselves? The Ku Klux Klan, as an organization, was certainly ‘cult-like.’ If the KKK is perceived as a religious organization, then their signature hood and robes are, quite literally ‘bad habits.’ But what does this say about the two figures in the painting? Could they simply be brainwashed, thinking that what they are doing is right, somehow?

This is one of the most terrifying realities that Guston confronts: that an evildoer rarely knows the extent of his actions. Indeed, it is this ignorance that makes such a person so dangerous. The Studio, painted one year before, depicts a cloaked Klansman creating a self-portrait. The painting portrays him exactly as he is, down to the stitching of his clothing and the three blood-red spots on the bottom of the canvas. The painting raises questions. Clearly the artist in the painting knows himself well, but does he know the extent of the evil that he is capturing? If he does know, what does he gain from admitting it? And it’s a painting of a self-portrait—was it created to depict Guston himself? Could the artist be expressing his fear of the evil that might exist within him? If he were evil, how would he know?

Philip Guston, The Studio, 1969.

Baring the worst part of oneself is freeing for an artist—once a guilty secret is out in the open, it loses its power. And to the viewer, there’s something deeply compelling about these paintings. It’s almost as if they’re trustworthy, somehow. Guston’s secrets are laid bare, and he pulls no punches. There’s no mystery here—it’s clear that the artist has nothing to hide. The candor eases our minds. These are the type of paintings that can make a sleepless night less painful.

If you, like Vic Chesnutt, seek refuge in the shocking and dark and grotesque, Guston’s work is a gift. It’s a mirror, a look into an artist’s psyche just as harrowing as a Klansman’s self-portrait. When we look at it, we see ourselves staring back at us. Consider the exhibit’s title: “What Kind of Man Am I?” It’s fitting—is this not the very question that the artist is asking us? Isn’t it the question we ask ourselves when we’re tossing and turning, unable to sleep, our unfinished work repressed from the surfaces of our minds but still vengefully stewing in its depths? The point of art is to acquaint us with reality. Vices and varicose veins are just as much a part of life as meadows and flowers. When we bare our wounds for the world to see, we heal. So what if we’re not always comfortable with what we find? Does a painting have to be ‘pretty’ to be beautiful?