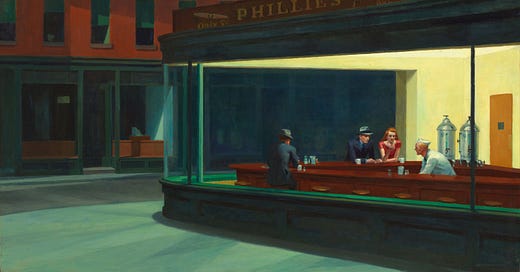

A lot of people dream of moving to New York City; I spent a good portion of my life wishing to escape it. It makes sense—wanderlust strikes everywhere, not only in small towns. Still, lately I’ve come to realize why so many people move here from afar, why this city is touted as a haven for artists and eccentrics, the subject of songs and paintings and films and fantasies. Although the days of finding a $20/month apartment in Greenwich Village are long gone, and twenty-five-cent meals from ‘automats’ with vending-machine-lined walls have been replaced with Amazon stores bearing four-dollar waters and surveillance cameras that track your every move, there is a charm here that just refuses to die. Every time I think it has, I find something in my home city that cannot be found anywhere else in the world. This time, it was an exhibit at the Whitney Museum of American Art. “Edward Hopper’s New York”: a stunning, massive collection of Hopper’s artwork, spanning his entire career, from the late 1800s/early 1900s, all the way until the 1960s, the decade of his death. The exhibit closed yesterday, but it left something behind.

It was remarkable to see. I was unfamiliar with Hopper previously; I went because a friend invited me. When telling me about the collection, she said that he was an artist that really makes you think. This intrigued me, and I was not disappointed. In fact, I’d never had such a contemplative reaction to a collection of artworks before.

I’m reminded of a G.K. Chesterton quote from his Autobiography, regarding impressionism:

“[Impressionism’s] principle was that if all that could be seen of a cow was a white line and a purple shadow, we should only render the line and the shadow; in a sense we should only believe in the line and the shadow, rather than in the cow.”

Chesterton had a long-standing bone to pick with impressionism. In his novel The Man Who Was Thursday, he called it “that final skepticism which can find no floor to the universe.” I always found this position surprising. Impressionism is one of the most beautiful art styles. I understand what he means, though. Yes, a colorful, dotty landscape is beautiful. But I’ve never felt compelled to stand and stare at one for ten straight minutes, creating a scene in my head about the past and what fills the subject’s mind, or just thinking about life and what the image implies about it. Yes, impressionists capture the essence of something large and distill it for their audience. But Hopper can see something small—something that an ordinary person might not consider at all, like a row of apartment buildings or a woman peering out of her window—and zoom in, capture every detail, capture motion. Capture a history, whether the subject is an aging ballerina sat on her bed looking somber, a couple having dinner at a restaurant in New York City, or a bridge below a cloudy sky.

As I looked at these paintings of New York City buildings and New York City people, a tune started playing in my head. It was a line from Simon & Garfunkel’s song “So Long Frank Lloyd Wright”:

“Architects may come and architects may go and never change your point of view.”

Couldn’t we say the same about painters? Frank Lloyd Wright was, of course, a visionary architect, and I couldn’t help drawing a comparison between him and Hopper. Both masters of their craft, they each had the rare ability to imagine a structure, something that we all take for granted, and turn it into a story. And Hopper didn’t even have the liberty of changing the form of the buildings he painted! He just represented what he saw, and added something intangible. He truly shared Wright’s gift for altering perspective. It seems unbelievable. And yet hanging before me were the works of this genius who could change my entire conception of the world around me with a picture of a drugstore window. Suddenly New York was this vibrant, unique place with a rich history. Suddenly I was a part of that history, standing in a gallery full of these paintings in the city where they were born. My point of view was changed; the art left me feeling happy.

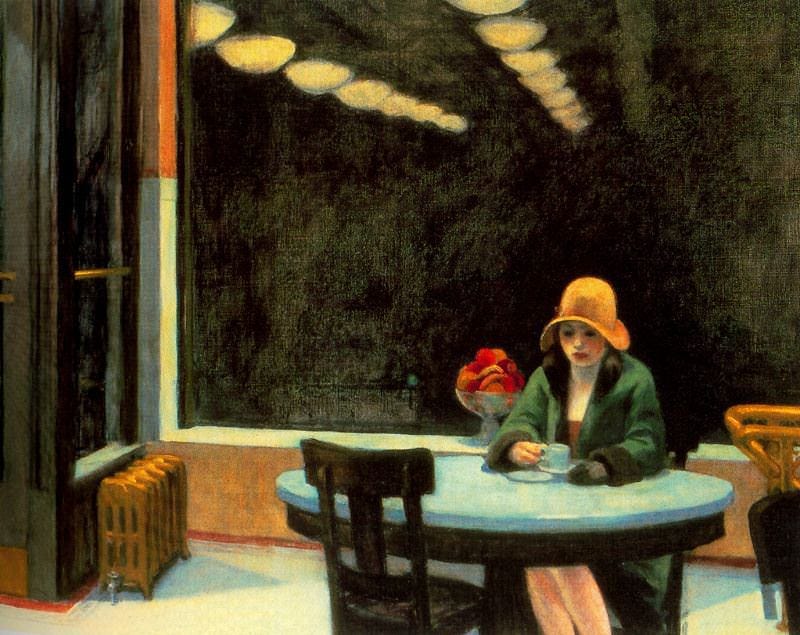

It’s interesting that great art can have this effect. There’s certainly nothing optimistic about Hopper’s work. In fact, one of the first remarks my friend made to me when we entered the gallery was that the paintings had an eerie sort of feeling to them, and that all of Hopper’s subjects looked lonely. She was right. All of the faces had a sullen, distant look. The soft sorrow of the girl sitting alone at a table in Automat; the man in Office in a Small City staring out of a large concrete office building. Trapped in a cage within a cage—the oppressive concrete office building, and then, ultimately, the picture’s frame.

Looking at the pitiful souls in these paintings, I noticed that as Hopper aged, the facial features he painted grew sharper. I wondered whether the harsh lines were intentional, or whether they were unconscious, channeling an aggression that Hopper had not felt before. It wouldn’t be the only transformation that his work had undergone. My friend pointed out that in his earliest paintings, the people actually interacted, whereas throughout most of his career his subjects hardly ever looked at one another, even on the uncommon occasion that there was more than one person depicted in a painting. She wondered what had changed in Hopper, remarked that he was happily married and had a successful career, and that he didn’t seem depressed. It didn’t occur to me until later that this aura of sadness was still there, even in these early paintings. It was expressed in the colors he used—lots of shadows and lots of black. The darkness merely got more sophisticated as he matured as an artist. Instead of channeling sadness through blacks and browns and degrees of abstraction, he created it with minute detail, in a distant expression on a woman’s face, or an orange sunset that casts an eerie shadow on a building’s facade. It’s interesting, how much more effective this subtle technique can be.

This doesn’t fully address her question, though—where did the darkness come from? Was it Hopper’s own unhappiness? Perhaps. But perhaps not. Some of Hopper’s paintings appear happy. The Girl at a Sewing Machine looked perfectly content with what she was doing. So did the horseback riders of Bridle Path. So did his wife, in the various portraits he created depicting her painting or reading. In fact, I didn’t see a single one in which she looked sad. The subject of his painting New York Movie—an usher standing in the corner of a crowded theatre looking somber—was based on his wife. In the initial study he drew of her, she was smiling. He doesn’t strike me as an unhappy man. And his subjects who were engrossed in their actions did not appear unhappy, either. Is he saying that the tragedy of city life lies in dormancy? The ennui of a woman in the corner of a theatre retreating into herself, or a man in an office building, absently looking out the window? Could the emotion they are expressing then be simply boredom, rather than anguish?

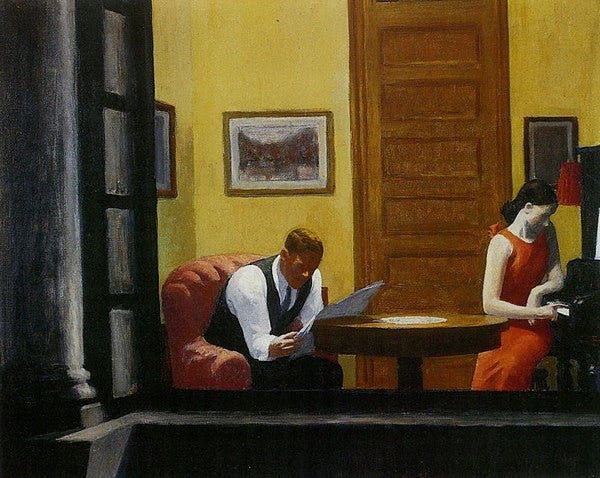

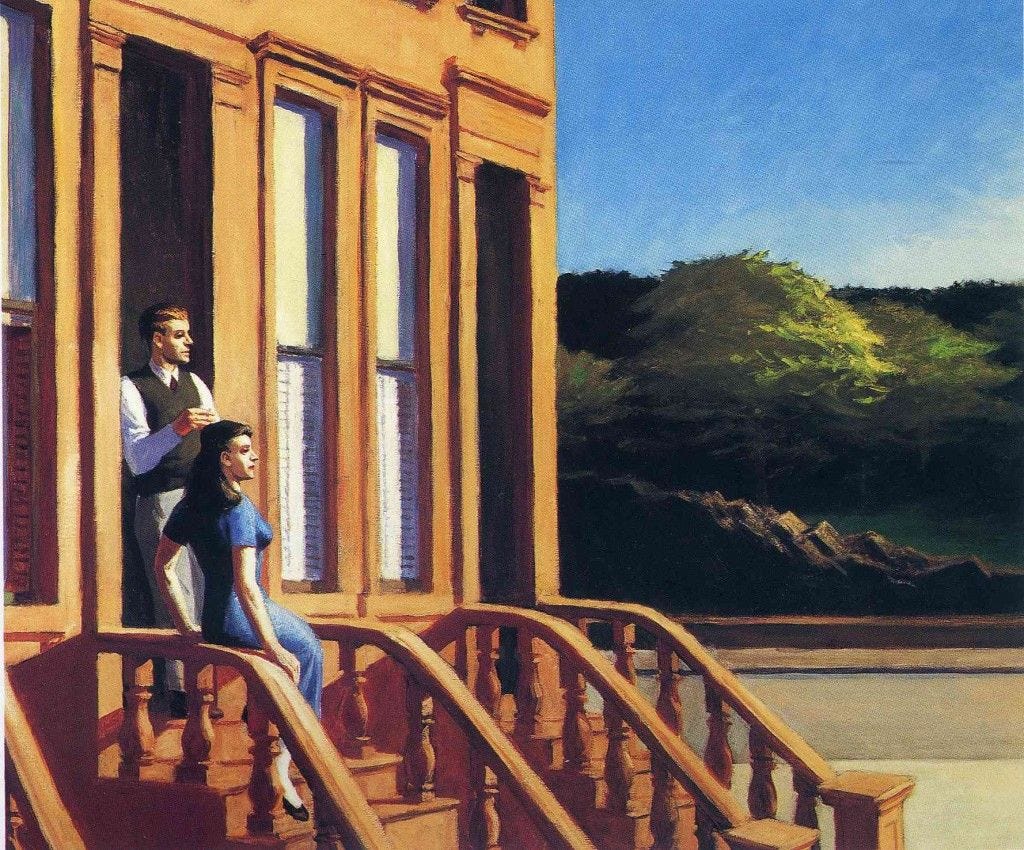

Perhaps it is a little bit of both, a gift from his keen artist’s eye, which sees the world exactly as it is. And the world is not merely sorrowful or merely bright, but instead a complex mandala of every point on the spectrum. This is what Hopper captures in his paintings, which might be why they feel so intimate. We have the simple beauty of a domestic scene (Room in New York), husband reading the newspaper, wife absently stroking the keys of a piano, dressed attractively, with paintings adorning their walls. A gorgeous brownstone at dawn (Sunlight on Brownstones), the clear sky presenting as a stunning gradient of blue, Central Park in the distance with its rocks and pillowy treetops, a couple taking in the atmosphere from their stoop. These paintings seem idyllic, when described this way. It’s only when the twist is revealed that they take on their ‘creepy’ quality. There’s a shadow in the corner of the Room in New York, obscuring the pillar that signifies the couples’ wealth. Neither couple is interacting—the women look sunken and sullen, the men tense with thought. The couple from Sunlight on Brownstones are not looking at the park, but at something else outside the painting. And there is something off about their relationship—a distance between them, despite their close proximity.

I was reminded of another Simon & Garfunkel song: “The Dangling Conversation.” In fact, this song started playing in my head the second I laid my eyes on Room in New York. Its elegant lyrics tell the story of a couple grown apart, atop beautifully finger-picked guitar:

“And we sit and drink our coffee Couched in our indifference, like shells upon the shore You can hear the ocean roar In the dangling conversation And the superficial sighs The borders of our lives.”

It’s the saddest song I’ve ever heard—of love lost, not in anger or betrayal, but negligence, staleness. It’s terrifying; it feels so real. Yet, without listening to the lyrics, it sounds merely beautiful. It’s like the paintings, which, without their enchanting quality that forces you to analyze them further, might strike their viewer as pleasant. The unsettling nature of these works of art lies in the grey area in which they dwell, somewhere between sorrow and paradise. They’re too complex; we can’t tuck them into neat categories in our minds and forget about them. Many people live their lives willfully blind to this multifaceted nature of reality. Great art compels us to open our eyes.

I wonder if the songwriters were inspired by Edward Hopper. It’s certainly possible; “The Dangling Conversation” came out in 1966, only ten years after Sunlight on Brownstones (and a year before Hopper’s death). It’s even possible that they’d met. However, they may have never crossed paths at all. Maybe their art gives me a ‘familiar’ feeling simply because they breathed the same air. There’s something lonely about living in a big city. Somehow, solitude is more existential when you are amongst a crowd of people. Yet Hopper does not paint crowds, and the ‘loneliest’ of his paintings do not depict anyone at all. Maybe, in his case, it’s the expectation of a crowd that gets us. Our brains associate them with the city imagery, so there is something jarring about the reality of a lonely Sunday afternoon at a coffee shop, or a quiet street at dusk. Perhaps the emptiness is us trying to fill in the empty space. Then why would we get this feeling from Simon & Garfunkel’s music? Maybe there is something uniquely gloomy about New York City, something intangible that lives in the brickwork and the skies and the residents with their sharp cheekbones and far-off gazes.

Despite this somber aura, we did not leave feeling sad. My friend found the paintings nostalgic. Hopper was her mother’s favorite artist; she’d seen these paintings in books and spread-apart in various galleries throughout her life, before finally seeing them all in one place. They reminded her of her own life, too. She had visited the last remaining automats when she was a young girl (known to her childhood self as “the place where you put the quarter in the wall”). She recognized many of the locations from the paintings. To her, the paintings felt like home.

To me, they felt like a strange, sleepy comfort that I couldn’t quite pinpoint. I love ‘gloomy’ art. There’s something freeing about acknowledging the darker side of life. It makes everything seem more okay, when hushed realities are allowed to make themselves known. And Hopper’s paintings aren’t ‘gloomy’ or ‘dark’ anyway. They are raw, powerful, and strikingly beautiful. He was interested in realism, and he executed it perfectly. He captured the world exactly as he found it—all its simplicities and multiplicities and magic.

We can all learn a lot from him.