Warning: this post contains spoilers for the movie Spirited Away.

It’s rare to stumble upon a story that truly speaks to you, and when it happens, the story is usually simple. No complex, mind-bending story arcs. No gimmicks or twist endings. Just an impactful message, a great plot, and some memorable characters.

We’re always trying to make history, do something that’s never been done before. The reason for this is that most of us don’t think we want to hear story we’ve already heard before. Plus, publishing trends change, peoples’ tastes change, and something that is a bestseller one year might completely fall flat the next based on factors that are completely out of an author’s control. However, when we separate ourselves from all of this, there are a few tricks of the trade, a few plot structures that never fail to speak to people no matter how many times they’ve been seen before.

It’s a cliche of its own at this point that Shakespeare wrote all the stories that it’s possible to tell and that we’ve all been repurposing the same ones ever since. Other people say this about the Greek playwrights. The statement is blatantly untrue. We can tell stories about an infinite number of things, and we can structure these stories in an infinite number of ways. However, let’s say we want to tell a good story. In that case, our possibilities narrow substantially.

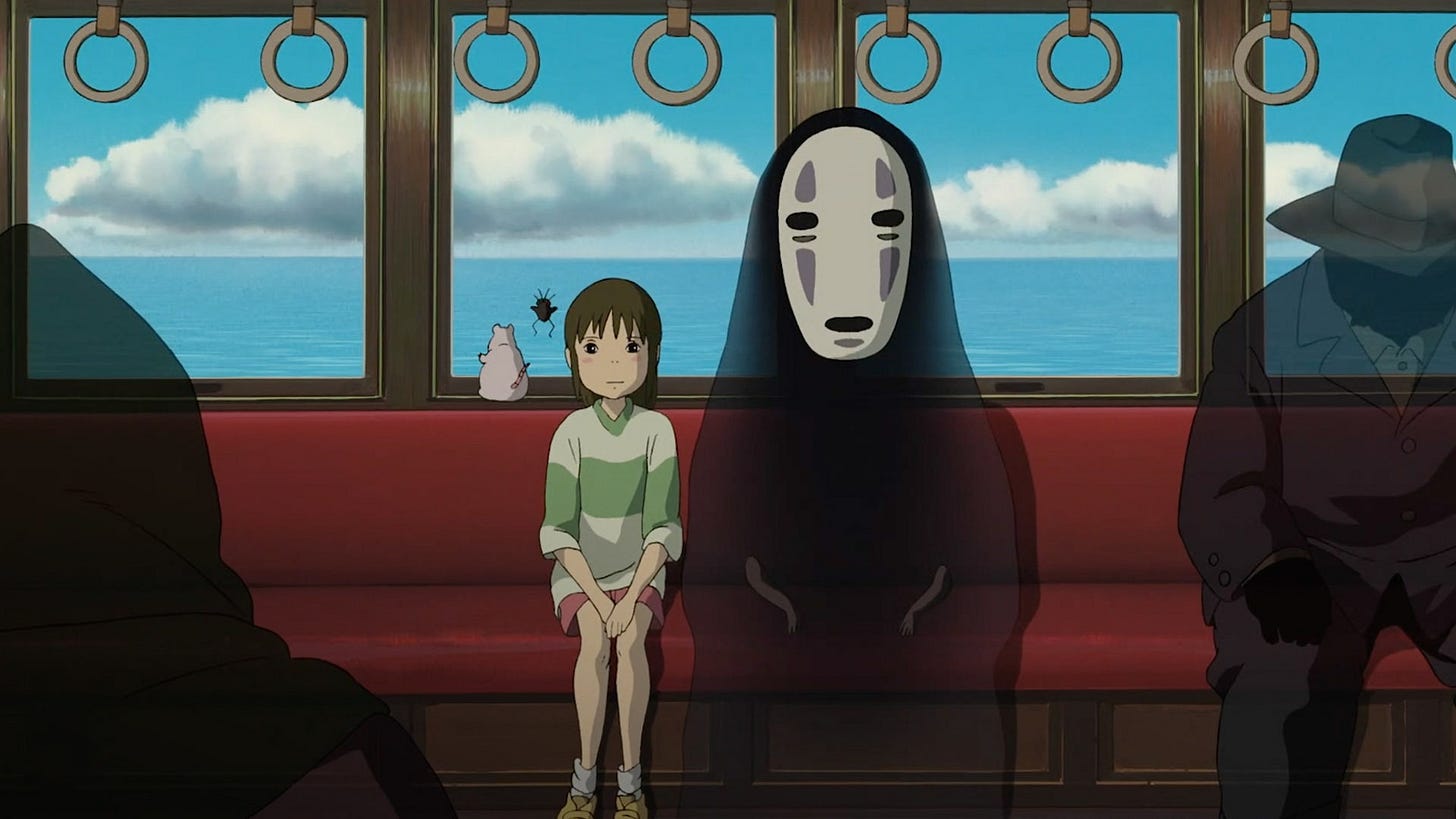

Over the weekend, I watched Hayao Miyazaki’s Spirited Away, a classic which is heralded as one of the greatest films of all time.

It’s your standard “portal fantasy”: a character stumbles upon a portal to another world, and her primary objective is to get back home. I recently found out that the genre is actually frowned upon by some snobby book-publishing people for being ‘unoriginal.’

It’s interesting to even use the word ‘unoriginal’ when referencing a film with an eerie yet vibrant world, distinctive and compelling characters, and a zany yet moving plot that kept me on the edge of my seat throughout its entire two-hour runtime. However, none of the things I just referenced are particularly new. This isn’t the first evil witch to serve as a villain of a children’s story. Although the details of Miyazaki’s world are unique, his isn’t the first imagining of a ‘portal to the spirit world.’ And most of the characters are based at least in part on Japanese mythology.

The hero’s motivation (to save her family and get home) is a rather common one, and the way she achieves this is perhaps even more so. She makes allies by being selfless, avoids a trap by not being greedy. And at the end of it all, it’s love that saves the day.

One of the things that stuck with me the most about the story was its clear-cut morality. Good people always get what they deserve in the end. Life isn’t easy, but challenges can be overcome with hard work and courage.

Suspense does not require novelty. When you’re watching a movie for children, you know that the hero is going to pull through somehow, and that the ending, while sometimes bittersweet, will always put the main character in a better place than where they were before. The job of a writer isn’t to subvert your expectations but to suspend your disbelief, to make you forget what you already know and entrap you within the story as it is unfolding.

There’s a formula for this. It’s called the hero’s journey, and it has been outlined in a number of ways. Joseph Campbell outlined seventeen steps of the hero’s journey in his book The Hero With a Thousand Faces. In The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers, Christopher Vogler identified twelve. Look it up yourself if you’re interested.

Essentially, the hero’s journey is this: an ordinary guy (or gal) is thrust into a unique situation. She’s scared. However, she learns that she has no choice, and with the help of a wise guide (e.g. Haku in Spirited Away), she embarks on her quest. It’s wrought with danger. She meets challenges, experiences failure. However, as her enemies get stronger, so does she. She develops courage, makes friends. When she reaches her biggest hurdle yet, she’s ready, and using the strength she has gained from her journey (and the allies she’s made along the way), she prevails. The way back is not easy, but when she returns home, she is triumphant. Whether the ‘gift’ she brings home with her is an actual item (like the hair tie Chihiro receives from Zeniba), a cure of some sort that they can share with the people back home, or just the memory of a great experience, our hero is enriched, somehow.

The hero represents our ideal. She is the person that we all wish we could be, that we channel when we’re at our best and idolize when we’re at our worst. When we emulate the mythical hero, good things happen for us. When we don’t, our luck sours.

One might argue that real life is seldom as clear-cut as the land of myths. Modern tales such as A Song of Ice and Fire subvert the traditional hero’s journey, communicating the message that virtue is a thing for fools, and that in real life, the villains win. This may be attractive to us. George R. R. Martin’s story took the world by storm, after all. However, it never came to a satisfying end. Perhaps ending such a story is impossible. How can a cruel, moral-less world ever lead to anything but destruction?

Perhaps this is where reality departs from myth, and the failure for nihilistic stories to truly move us is merely proof that fiction can never become fact, and that escapism will always be more attractive than harsh truth.

However, the point of fiction is to communicate truths about the world that are difficult to communicate directly. Is it possible that, in some elusive way that the modern world has become too jaded to understand, the hero’s journey is more ‘real’ than what we consider real life?

Mythological villains are victorious for a long time before they meet their rightful end—if they weren’t, there would be no story. Perhaps, when we assume that real life doesn’t follow the pattern of myths, we’re just not thinking big enough. Maybe, just maybe, our innate need to believe in heroes is evidence that this eternal myth is actually true.

Thank you for reading. If you enjoyed this post and would like to support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

You can also buy me a coffee. Or send me on a magical journey of self-discovery for which a nice, steaming-hot cup of coffee will be my eventual reward.

"Perhaps...when we assume that real life doesn’t follow the pattern of myths, we’re just not thinking big enough. "

Hum. Food for, deep, thought.

I loved this!