Who Wants to Save the World?

"Watchmen" and the pitfalls of well-intentioned evil

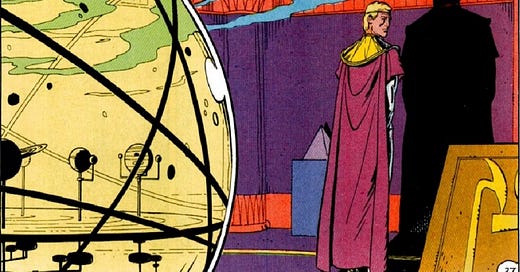

This month, I reread the graphic novel Watchmen.

It’s always a unique experience rereading one of your favorite books—especially a book of Watchmen’s grandiosity. The ‘explosive’ ending (and its dark consequences). The way the story manages to capture everything about human nature, the nature of reality, the nature of, well, nature. The impressive feat of bringing all the ‘moving parts’ together to form such a story in the first place.

We can see this in the way the author examines time. Through the lens of the superhuman character Dr. Manhattan, he posits a strange, nonlinear model of time, suggesting that our lives are not comprised of a long, impermanent string of moments, the way we typically conceptualize it, but is instead a fully-formed structure in which control is, at least to some extent, illusory. The structure exists in totality—we, in our limited capabilities of perception, have to view one moment at a time.

It’s a strange, rational concept of the way things are. It suggests that things are, to some extent, preordained. Although the story suggests some sort of fluidity in this concept, it posits that there are still some ‘laws’ that govern things.

In fact, Watchmen is very orderly in that way. It seems that when writing the book Alan Moore understood that there are certain parameters which reality must stay within. The story abides by the laws of time, of physics. It provides an in-depth look at the laws of human nature, and its relationship to the (completely illusory) laws of justice. The main ‘problem’ examined in the book seems to be examining a different law, one that is harder to define. One might call it the ‘law of the universe’ itself—the fact that nothing is permanent, and everything must change.

It’s so obvious a statement that it is almost a platitude. You’ve heard this principle touted a million times: ‘nothing lasts forever,’ ‘this too shall pass.’ It’s one of those things that’s so true it’s basically lost all meaning. However, despite having been reduced in our collective consciousness to a mere cliche, it is the undercurrent which governs all of life (and, rightly, all of Watchmen).

Think of the very conflict that the book describes—the possibility of nuclear Armageddon, the impending ‘end of the world.’ Is all of this not a direct result of change?

Consider the entry from Rorschach’s journal on the first page of the book:

“They had a choice, all of them. They could have followed in the footsteps of good men like my father, or President Truman. Decent men, who believed in a day’s work for a day’s pay. Instead they followed the droppings of leches and communists and didn’t realize that the trail led over a precipice until it was too late.”

Interestingly, the line hits just as hard in 2023 as it probably did in 1986. Perhaps this is a testament to just how far our society has fallen since the ‘golden age’ that Rorschach speaks of. However, isn’t it also possible that there has always been bad in the world, that every generation has lauded the one that came before it and scorned the one that came next, that people have been foretelling Armageddon since the beginning of time?

What ‘great men’ was Rorschach talking about, exactly? Sure, the early 1900s saw the men who fought bravely in the First and Second World Wars. There were also the men who started it. Is he talking specifically about the decline of the hardworking American spirit? Sure, that is a serious problem, but the world he wished to preserve wasn’t perfect. There was poverty—surprisingly more so than there is today, after the decline of such ideals. One might argue that there was a tradeoff there, and that what we have now is worse. Who’s to say? The world has never been perfect, and it never will be.

Still, Adrian Veidt, as he revealed his horrifically well-intentioned plan, remarked: “Somebody has to save the world.”

Has there ever been a generation that didn’t think the world needed saving?

It’s like a paradox—nothing stays the same and everything stays the same at the same time. Or, in other words, the people in the world change, the circumstances change, but the laws—such as the fact that there will always be both good and evil in the world—will remain. Closely tied to this is another paradox: that the greatest evils are committed with the best of intentions. That, by trying to save the world, you are more likely to destroy it than if you just leave everything alone.

This isn’t just some abstract idea—you can see it made manifest time and time again throughout history. Think about the disaster of communism, all of the countless lives lost in Soviet Russia. The movement was co-opted by evil, for sure, but the catalyst for all of the carnage was positive social change! People saw the things that were not perfect about their world, such as wealth inequality, poverty, long working hours, even starvation, and they wanted to change it.

What happened? Each change opened up a ‘can of worms.’ It turned out that the workers couldn’t actually run the farms or the factories on their own, and that by murdering everyone who knew how, they ensured that everyone would starve. Instead of elevating themselves, they pulled everyone else down. And it was all motivated by hate! The Soviets convinced their peasant class to kill the people who had slightly more than them by convincing them to hate them—so much so that they decided that they were unworthy of life. The same type of propaganda happened in Nazi Germany. It’s still happening in places in the world today—we might even be able to spot some of it right at home.

Adrian Veidt isn’t a Socialist revolutionary, convinced that one last war will finally bring about peace, but shares some characteristics with this type of figure. He’s an idealist, a utopian dreamer—he believes that it is possible for the world to become a better place. He believes that some blood may need to be shed in service of this ‘greater good,’ and that being the one to initiate the bloodshed is not only necessary but noble. Finally, he believes that he is the man for the job.1

Tales of the Black Freighter mirrors this. The protagonist is scarred by a terrible event, and convinced that his hometown is in peril. Motivated by good intentions, he decides that he will make it home by any means necessary. He becomes a monster, commits acts that he never would have dreamed of, loses his humanity. He murders innocent people. And when he gets there, he realizes the town never needed saving at all.

For all his good intentions, how many lives did the man from Black Freighter save?

How many lives did Veidt save by murdering half of New York?

Throughout history, how many lives have been saved by war or revolution?

The only way humans know how to ‘fix’ things is through violence. It’s because the evil that we seek to eradicate is within us—within all of us—and in a population tempted to sin, there are going to be some segment of the population that acts on this desire. What is a purported savior to do with these people? They’re more ruthless, willing to stoop to greater lows than the ‘good’ people. The only way to beat them is to reach down to their level. Eradicate them, by any means necessary. When all the evil people are gone, the world can finally be good.

When you become evil to end all evil, has ‘evil’ been eradicated, or just perpetuated? People don’t just wake up one morning and ‘decide’ to be bad. They just go about their lives and then look in the mirror one day and realize that they don’t recognize themselves. For whatever reason—fear, greed, hedonism, or (worst of all) misguided altruism—they just end up that way. It’s never the cheesy cartoon malice that we often see in stories with one clear hero and one clear villain.

Still, according to Veidt, “somebody has to save the world.” Is he right? If so, who’s qualified? Whose decision is that to make? And if the answer is: “nobody should ever save the world,” what’s the alternative? Saying “just leave things alone and they’ll work themselves out” is a moot point—it’s human instinct to want to get involved. The only way there could be ‘peace on Earth’ is if there were no people here. Perhaps we’re meant to continue this cycle of rot and rebirth. Maybe human society is like a phoenix—it gets old and frail after a while, and can only be reborn from its own ashes.

Veidt’s story leaves off with a conversation with Dr. Manhattan. He tells himself his actions were justified, but he doesn’t seem so sure. Veidt asks:

“I did the right thing, didn’t I? It all worked out in the end.”

Dr. Manhattan’s final reply: “‘In the end’? Nothing ends, Adrian. Nothing ever ends.”

I’ll leave you with the same thought.

Compare this with Raskolnikov’s motivation for murder in Crime and Punishment, the Thinking Man Book Club’s first novel.